Kaiser Permanente researcher receives $4.5 million NCI grant to study link between inflammation in the breast’s fatty tissue and breast cancer outcomes

By Sue Rochman

When an injury occurs, the body goes into action. The damaged tissue sends out the chemical messages that proclaim help is needed, and the white blood cells respond, initiating an inflammatory process designed to promote healing. After the damage is repaired, the white blood cells will retreat, and the inflammation will subside. At least that’s the way it is supposed to happen. But sometimes things go awry, and the inflammatory process gets kicked into gear even though no injury has occurred—and doesn’t stop. This chronic inflammation can  damage the DNA of nearby cells, increasing risk for certain types of cancers. In fact, studies have found associations between the level of circulating inflammatory markers and cancer initiation and development. These associations are thought to work both ways: inflammation may create an environment for tumors to grow, and cancer may cause inflammation.

damage the DNA of nearby cells, increasing risk for certain types of cancers. In fact, studies have found associations between the level of circulating inflammatory markers and cancer initiation and development. These associations are thought to work both ways: inflammation may create an environment for tumors to grow, and cancer may cause inflammation.

Typically, blood tests are used to measure circulating levels of inflammation, primarily for research purposes. Lawrence Kushi, ScD, research scientist at the Kaiser Permanente Northern California Division of Research, believes a more accurate way to measure the impact inflammation has on breast tumors is to study the breast tissue itself. Kushi recently received a $4.5 million grant from the National Cancer Institute (NCI) to advance this area of research.

The 5-year study will use mastectomy tissue samples and data collected from the Pathways Study of Breast Cancer Survivorship, a prospective study of women diagnosed with early-stage breast cancer at Kaiser Permanente Northern California hospitals between 2005 and 2013. Among this group of women, 39% (1,750) had a mastectomy as part of their breast cancer treatment. Kushi will investigate whether the incidence and severity of inflammation seen in the breast white adipose tissue (B-WAT) near the tumor affects breast cancer outcomes.

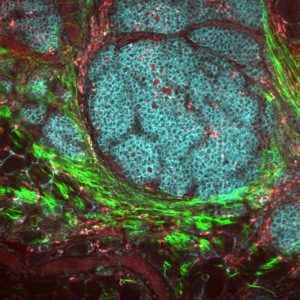

White adipose tissue is found throughout the breast. Under a microscope, the fat cells inside this tissue appear much larger than other breast cells. If the fat cells trigger an inflammatory process, they become surrounded by white blood cells, called macrophages. “The macrophages are trying to get rid of the inflammatory damage,” said Kushi, “and when this happens, you see the big round fat cell surrounded by little macrophages, so it sort of looks like a crown. We will be looking to see if these crown-like structures are present in the breast tissue near the tumor and, if so, how many of them there are.”

This information will provide a measure of the severity of inflammation in the breast tissue at the time of their mastectomy. Surveys completed by the women in the Pathways Study at the time of their breast cancer diagnosis will allow Kushi and his colleagues to also investigate potential associations between breast white adipose tissue inflammation and body composition and lifestyle factors, such as diet and exercise, which Kushi has studied previously.

Kushi will be conducting the study with Andrew Dannenberg, MD, at Weill Cornell Medicine, and Neil Iyengar, MD, at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, Chi-Chen Hong, PhD, at Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center, and Heather Greenlee, ND, PhD, MPH, at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center. Dannenberg and Iyengar’s previous research on breast white adipose tissue and breast cancer laid the groundwork for the new study. “While doing their research, Andrew Dannenberg and Neil Iyengar learned that in our Pathways Study we had been collecting surgical specimens that could be used to study non-tumor adipose tissue,” said Kushi. “First, we collaborated on a pilot project to see if we could measure B-WAT inflammation markers in a small subset of Pathway Study participants. Our success in the pilot study allowed us to apply for – and get – the NCI grant.”

The team expects to report initial findings within the next five years. The hypothesis is “there is a connection between levels of this inflammatory process and survival,” said Kushi. If that is the case, “it may be the inflammation in the adipose tissue in the breast is a measure we can add to what we currently use to assess prognosis.”

Division of Research co-investigators include research scientist Elizabeth Feliciano, ScD, SM, research scientist Marilyn Kwan, PhD, research scientist Bette Caan, DrPH, and research scientist Catherine Lee, PhD.

NCI Grant Details: Breast White Adipose Tissue Inflammation and Breast Cancer Outcomes

This Post Has 0 Comments