Kaiser Permanente study finds cancer and its treatments accelerate decline in physical function

Postmenopausal women with cancer report a greater decline in physical function than women who have not had cancer, new Kaiser Permanente research shows.

“We know that cancer is a disease of aging, and that as we grow older our risk of getting cancer increases,” said lead author Elizabeth M. Cespedes Feliciano, ScD, a research scientist at the Kaiser Permanente Northern California Division of Research. “What has only been appreciated more recently is that cancer and its treatments can actually speed up the biological processes that are associated with aging.”

The research published January 19 in JAMA Oncology is the largest to date to assess rates of decline in physical function — a key marker of aging — before and after a cancer diagnosis.

People with poor physical function have a higher risk of falls and greater difficulty with everyday tasks. It is also more difficult for them to live independently.

Cespedes Feliciano and her team used data collected through the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) — the landmark long-term national health study launched in 1991 at Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center — as well as data from the WHI’s Life and Longevity After Cancer (LILAC) study. Kaiser Permanente Northern California was an original WHI recruitment site and continues to have patients enrolled in the study.

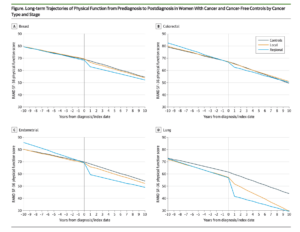

The new study compared aging in 9,203 WHI participants who had been diagnosed with breast, colorectal, lung, or endometrial cancer (the most common cancers in women) with 45,358 similar WHI participants who did not have cancer. The researchers analyzed data the WHI collected regularly on physical function — one key aspect of aging — as measured by responses to questions about activity level, strength, and self-care.

“The Women’s Health Initiative is a unique resource because it has been collecting data on women for decades,” said Cespedes Feliciano. “It wasn’t designed to study cancer survivors, but the data they collected gave us the opportunity to assess the effect that cancer had on rates of decline in physical function both before and after their cancer diagnosis, and then compare that to the rates of decline that occur with usual aging in women without cancer.”

The study found that across all cancer types decline in physical function occurred more rapidly after treatment began, with variations tied to both the location of the cancer and the treatments received. The steepest decline in physical function was seen in women with lung, endometrial, or colorectal cancer that had spread from where it had started to nearby lymph nodes, tissue, or organs. In these women, a decline in physical function was seen even before their cancer diagnosis.

The study found that across all cancer types decline in physical function occurred more rapidly after treatment began, with variations tied to both the location of the cancer and the treatments received. The steepest decline in physical function was seen in women with lung, endometrial, or colorectal cancer that had spread from where it had started to nearby lymph nodes, tissue, or organs. In these women, a decline in physical function was seen even before their cancer diagnosis.

For women with breast cancer that had spread to nearby lymph nodes, declines in physical function occurred at nearly 4 times the rate seen in women who did not have cancer. For women with localized breast cancer, declines in physical function occurred at twice the rate seen in women who did not have cancer. For women with endometrial cancer, the decline was steeper for women whose treatment included chemotherapy than it was for women who received only radiation.

“One of the most unusual and valuable aspects of these analyses is the ability to look at the experiences of women with cancer both before and after their cancer diagnoses in comparison to similar women who remained cancer free,” said Garnet Anderson, PhD, senior author and Principal Investigator of the WHI Clinical Coordinating Center. “This allows us to measure in a reliable way the impact of cancer and its treatment on physical function, separate from normal aging.”

Scientists have previously shown that both cancer and its treatments speed up biological markers of aging in cells, tissue, and mice. These findings create a biologically plausible explanation for the hastened aging seen in the new study.

“The changes that occurred in the first year, especially for women with cancer that had begun to spread regionally or who received a systemic treatment, like chemotherapy, were profound,” said Cespedes Feliciano. “This might be, in part, because chemotherapy both kills tumors and damages normal cells in ways that affect mechanisms that are associated with aging.”

Ultimately, even at 5 years post-diagnosis, survivors of most cancer types had physical function levels that remained below those seen in women of the same age who were cancer-free. Raymond Liu, MD, an adjunct investigator with the Division of Research and the director of cancer survivorship for Kaiser Permanente San Francisco, said the findings confirm what is commonly seen in clinical practice.

“This study helps quantify the degree of worsening in physical function in different cancers,” said Liu. “It also highlights the importance of our current efforts at Kaiser Permanente to screen for decline in physical function in our cancer population and intervene when a decline is noted. I would encourage patients who have developed advanced cancer to work with their care teams to establish achievable rehabilitation goals.”

Cespedes Feliciano said she intends to conduct further research that builds on these findings. “The first step is to show that this accelerated aging in physical function happens and persists over time, which is what this study did,” she said. “Now, we want to see if we can identify early predictors of this accelerated aging. If we can, we might be able to identify the women who might benefit most from rehabilitation programs for cancer survivors or even develop interventions during the treatment period to mitigate aging effects.”

The study was funded by the National Cancer Institute.

Co-authors include Charles Quesenberry, PhD, and Bette J. Caan, DrPH, of the Division of Research; Garnet Anderson, PhD, Sowmya Vasan, MS, and Ulrike Peters, PhD, of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center; Juhua Luo, PhD, of the University of Indiana; Alexandra M. Binder, ScD, of the University of Hawaii; Rowan T. Chlebowski, MD, PhD, and Kathy Pan, MD, of the Lundquist Institute; Hailey Banack, PhD, of the University of Buffalo; Electra Paskett, PhD, of The Ohio State University; Grant R. Williams, MD, MSPH, of the University of Alabama; Ana Barac, MD, PhD, of Georgetown University; Andrea Z. LaCroix, PhD, and Aladdin H. Shadyab, PhD, MS, MPH, of the University of California, San Diego; Kerryn W. Reding, PhD, MPH, of the University of Washington; and Lihong Qi, PhD, of the University of California, Davis.

# # #

About the Kaiser Permanente Division of Research

The Kaiser Permanente Division of Research conducts, publishes and disseminates epidemiologic and health services research to improve the health and medical care of Kaiser Permanente members and society at large. It seeks to understand the determinants of illness and well-being, and to improve the quality and cost-effectiveness of health care. Currently, DOR’s 600-plus staff is working on more than 450 epidemiological and health services research projects. For more information, visit divisionofresearch.kaiserpermanente.org or follow us @KPDOR.

This Post Has 0 Comments