Kaiser Permanente study suggests ties among mutation type, tumor location, and survival

A Kaiser Permanente study suggests that the prognosis of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer may be determined at least in part by whether the tumor has a specific type of mutation — but in an unexpected way.

The study, published November 29 in the Journal of Clinical Oncology, included 1,043 Kaiser Permanente Northern California (KPNC) patients with metastatic colorectal cancer whose tumors had undergone next-generation sequencing, a process that can detect mutations in more than 400 genes. The researchers identified 735 patients who had a tumor with a mutation in a tumor suppressor gene called p53.

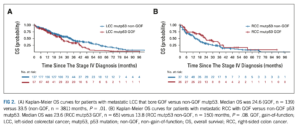

The research team divided the 299 different p53 mutations found in the tumors into 2 types: gain-of function, which allow the p53 proteins to act in new ways, and non-gain-of-function. They also looked at whether the patient’s tumor had started on the right side or on the left side of the colon. Their analyses showed that patients with metastatic left-sided colorectal cancer had poorer survival if they had a gain-of-function p53 mutation whereas patients with metastatic right-sided colorectal cancer did not. The study also showed that survival for right-sided colorectal cancer was worse than for left-sided colorectal cancer only among the patients with non-gain-of-function p53 mutations.

“Over the past 30 years, there have been many, many studies on p53 mutations in colorectal cancer, but no one has shown whether p53 mutations are associated with worse or better survival using state-of-the-art comprehensive genetic sequencing,” said the study’s lead author Minggui Pan, MD, PhD, an adjunct investigator with the Kaiser Permanente Division of Research and an oncologist with The Permanente Medical Group (TPMG). This is the first study to find an association of p53 mutations with survival — but with differences based on the anatomical location of the tumor. This is both exciting and unexpected.”

“Over the past 30 years, there have been many, many studies on p53 mutations in colorectal cancer, but no one has shown whether p53 mutations are associated with worse or better survival using state-of-the-art comprehensive genetic sequencing,” said the study’s lead author Minggui Pan, MD, PhD, an adjunct investigator with the Kaiser Permanente Division of Research and an oncologist with The Permanente Medical Group (TPMG). This is the first study to find an association of p53 mutations with survival — but with differences based on the anatomical location of the tumor. This is both exciting and unexpected.”

The p53 gene is called a tumor suppressor gene because the protein it produces is akin to a brake pedal; it controls how fast a cell divides. When a p53 gene develops a mutation, it begins to produce proteins that don’t act the way they should. More than half of all colorectal cancers have a p53 mutation.

We had expected gain-of-function mutations to be associated with worse survival, but that wasn’t the case with right-sided colorectal cancers.

— Minggui Pan, MD, PhD

The type of p53 mutation that develops will affect how the protein works. Gain-of-function mutations cause the gene to produce proteins that act like a gas pedal instead of a brake pedal, fueling cancer growth. Of the 735 patients in this study with a tumor with a p53 mutation, 204 had a gain-of-function mutation.

About 2 out of 3 colorectal cancers begin on the patient’s left side, which is made up of the descending colon, sigmoid colon, and rectum. In general, left-sided tumors tend to have a better prognosis than right-sided tumors, which develop in the cecum (the pouch where the large intestine begins) or the ascending and transverse colon. It is not clear why right-sided colorectal cancer has a worse prognosis than left-sided colorectal cancer.

“When I first saw the survival curves, I thought I had made a mistake when I input the data,” said Pan. “But I kept checking, and it wasn’t a mistake. And then I got really excited about the finding. We had expected gain-of-function mutations to be associated with worse survival, but that wasn’t the case with right-sided colorectal cancers.”

Why a gain-of-function p53 mutation would affect left-sided and right-sided tumors in a different way is not known. “Science is an iterative process,” said the study’s senior author Laurel A. Habel, PhD, a senior research scientist at the Division of Research. “If replicated in other patient studies, we expect these findings will encourage biologists to investigate the mechanism of why these different types of mutations affect cancers on opposite sides of the colon in different ways. Then, we hope to use their findings to guide our future research.”

If the findings are confirmed, it could help researchers better assess treatments in clinical trials and help physicians treat patients with colorectal cancer. “A number of biomarkers are already used in colorectal clinical trials and in making treatment decisions,” said Pan. “Based on our results, I expect we will see new interest in investigating whether p53 gain-of-function and non-gain-of-function mutations could also be a useful biomarker for estimating prognosis.”

TPMG supported this research through funding for a collaborative program with Strata Oncology. Pan and Habel are part of the KPNC Genomic Oncology Committee that reviews all tumor sequencing reports sent across the region. Over the past 3 years, over 13,000 KPNC patients have had their tumors sequenced. This data base is regularly analyzed by the Genomic Oncology Committee, and they have presented and published their analytic results at national oncology meetings such as ASCO and the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

Co-authors include Chen Jiang, PhD, Pam Tse, BA, Ninah Achacoso, MS, Stacey Alexeeff, PhD, Aleyda V. Solorzano, MD, and Elaine Chung, MA, of the Division of Research; Thach-Giao Truong, MD, Amit Arora, MD, Tilak Sundaresan, MD, Jennifer Marie Suga, MD, and Sachdev Thomas, MD, of The Permanente Medical Group; and Wenwei Hu, MD, PhD, of Rutgers Cancer Institute of New Jersey.

# # #

About the Kaiser Permanente Division of Research

The Kaiser Permanente Division of Research conducts, publishes and disseminates epidemiologic and health services research to improve the health and medical care of Kaiser Permanente members and society at large. It seeks to understand the determinants of illness and well-being, and to improve the quality and cost-effectiveness of health care. Currently, DOR’s 600-plus staff is working on more than 450 epidemiological and health services research projects. For more information, visit divisionofresearch.kaiserpermanente.org or follow us @KPDOR.

This Post Has 0 Comments