Kaiser Permanente study finds racial and ethnic differences in medication initiation

For adults newly diagnosed with diabetes, getting blood sugar levels under control is the first goal. Guidelines recommend diabetes medications to help patients meet their target blood sugar range. Yet a new Kaiser Permanente study found that adults of certain racial and ethnic groups are less likely to start medication within the first year of diagnosis.

“We know there are race and ethnic disparities in diabetes-related health outcomes and that many factors contribute to these differences,” said the study’s co-lead author Anjali Gopalan, MD, MS, a research scientist at the Division of Research and a senior physician with The Permanente Medical Group. “With our growing awareness of the lasting benefits of early glycemic control, and the important role of medications in lowering blood sugar levels, we wanted to look at whether there are differences in early medication initiation by race and ethnicity — and there are.”

The study, published August 4 in the Journal of General Internal Medicine, included 77,199 members of Kaiser Permanente Northern California newly diagnosed with type 2 diabetes between 2005 and 2016. The researchers used the patient’s electronic medical records to determine if they were dispensed any diabetes medication during the year following their diagnosis. Self-reported race and ethnicity information was used to separate the members into 12 groups.

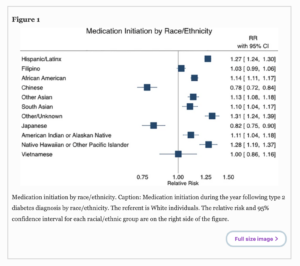

The study showed that, overall, 47% (36,283) of the adults started a glucose-lowering medication during the first year following their diagnosis. However, initiation rates varied widely by group: 32% of Chinese adults and 35% of Japanese adults started taking a diabetes medication compared to 44% of white adults, 50% of Black adults, 56% of Hispanic/Latinx adults, and 58% of individuals of other racial or ethnic groups.

“Seeing that Black and Latinx adults had higher than average initiation rates intrigued us because, overall, these groups tend to have higher rates of diabetes-related complications,” said Gopalan. “Our findings also suggest we need to better understand the factors that may be keeping Chinese and Japanese adults from starting medication after their initial diagnosis.”

If we don’t understand what is driving the treatment differences we are seeing, we don’t know if the decisions are clinically appropriate.

— Anjali Gopalan, MD, MS

The study found that among adults newly diagnosed with diabetes who had high HbA1c (blood sugar) levels — a group for whom it is clear medication should be started — there was little difference in medication initiation between race and ethnic groups. In addition, race and ethnic differences in medication initiation did not meaningfully differ among individuals based on their age at diagnosis, body mass index (BMI), socioeconomic status, and the presence of other ongoing health problems.

“Diabetes treatment is tricky as it is not one size fits all,” said Gopalan. “But if we don’t understand what is driving the treatment differences we are seeing, we don’t know if the decisions are clinically appropriate or if they are rooted in provider implicit biases or patient misconceptions about the risks and benefits of medication.”

“Diabetes treatment is tricky as it is not one size fits all,” said Gopalan. “But if we don’t understand what is driving the treatment differences we are seeing, we don’t know if the decisions are clinically appropriate or if they are rooted in provider implicit biases or patient misconceptions about the risks and benefits of medication.”

“As a physician, I want every patient to understand that having to take medication is not an indicator of how bad your diabetes is, or a sign that you have failed at making important behavior changes,” she added. “Medications are just another tool in diabetes management that can help keep patients healthy and prevent complications.”

The study was funded by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities, the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, and the National Institute on Aging.

Co-authors include co-first author Aaron N Winn, PhD, of the Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee; Andrew J Karter, PhD, of the Division of Research, and Neda Laiteerapong MD, MS, of The University of Chicago.

# # #

About the Kaiser Permanente Division of Research

The Kaiser Permanente Division of Research conducts, publishes and disseminates epidemiologic and health services research to improve the health and medical care of Kaiser Permanente members and society at large. It seeks to understand the determinants of illness and well-being, and to improve the quality and cost-effectiveness of health care. Currently, DOR’s 600-plus staff is working on more than 450 epidemiological and health services research projects. For more information, visit divisionofresearch.kaiserpermanente.org or follow us @KPDOR.

This Post Has 0 Comments